NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

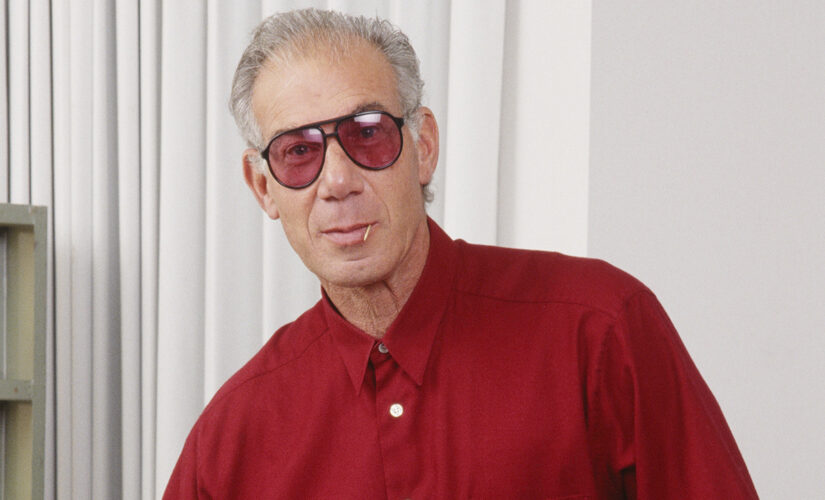

Bob Rafelson, the director, producer and writer who brought a European sensibility to American filmmaking with “Five Easy Pieces” in 1970, died Saturday evening at his home in Aspen, Colorado. He was 89 years old.

Rafelson’s death was confirmed by his former personal assistant of 38 years, Jolene Wolff, who worked under Rafelson’s production banner Marmont Productions. Wolff stated that Rafelson died peacefully, surrounded by his family.

The Monkees vocalist and drummer Micky Dolenz, the final surviving member of the music group, offered a statement on Rafelson’s death Sunday afternoon.

“One day in the spring of 1966, I cut my classes in architecture at L.A. Trade Tech to take an audition for a new TV show called ‘The Monkees.’ The co-creator/producer of the show was Bob Rafelson,” Dolenz said. “At first, I mistook him for another actor there for the audition. Needless-to-say, I got the part and it completely altered my life. Regrettably, Bob passed away last night but I did get a chance to send him a message telling him how eternally grateful I was that he saw something in me. Thank you from the bottom of my heart, my friend.”

MICKY DOLENZ, LAST SURVIVING MONKEES MEMBER, TO EMBARK ON TRIBUTE TOUR: ‘LIKE MY BROTHERS’

Bob Rafelson passed away on Saturday at his Aspen, Colorado, home.

(George Rose/Getty Images)

Rafelson partnered with Bert Schneider, who died in 2011, to form the production company Raybert, which later became BBS. He was a major behind-the-scenes force in the making of movies like “Easy Rider” in 1969 and “The Last Picture Show” in 1971.

But Rafelson’s production and direction of “Five Easy Pieces,” a critical success in America that garnered impressive box office abroad, turned him into a major player among a new generation of directors inspired by the style of the French New Wave. Director Ingmar Bergman voiced admiration for Rafelson’s achievement.

Starring Jack Nicholson as Bobby Dupea, “Five Easy Pieces” was a character-driven road movie reflecting Rafelson’s view of an outsider suffering from deep, undisclosed pain. In an interview, Rafelson, the son of a hat maker and abusive, alcoholic mother, said Dupea was a character in need of escape. “I had been trying to escape from my background since I was 14 years old,” Rafelson said.

Rafelson’s first three films signaled a new depth in American filmmaking. He looked at dysfunctional families, thwarted ambition and alienation in “Five Easy Pieces,” “The King of Marvin Gardens” in 1972 and “Stay Hungry” in 1976.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR THE ENTERTAINMENT NEWSLETTER

Jack Nicholson, Jessica Lange and Bob Rafelson at the Cannes Film Festival in 1981.

(Pool Laforet/Simon/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

“Five Easy Pieces,” nominated for four Oscars, including best picture, also heralded Nicholson’s arrival as a major star, earning him his first best actor nomination. Rafelson would also work with Nicholson as either co-writer or director on films including “The Postman Always Rings Twice” in 1981 and “Blood and Wine” in 1996. The actor said he considered Rafelson part of his “surrogate family.”

Ironically, Rafelson’s professional relationship with Nicholson began with much lighter fare. “Head” (1968), which the director co-wrote with Nicholson, starred the Monkees, a fabricated rock group modeled on the Beatles. They were just coming off the hit NBC series of the same name created by Rafelson and Schneider. The show ran from 1966-68, winning Rafelson an Emmy for comedy series in 1967.

Though income from the series would provide financing for “Easy Rider,” Rafelson said he hated what the success of “The Monkees” represented. He called “Head,” his first feature, a scornful attempt to “expose the project” for its slick, trendy superficiality. Rafelson later explained that he touched on so many genres in the film – adventure, Western, romance – because “I thought I would never get to make another picture.”

Robert Rafelson was born in New York City. His uncle Samson Raphaelson (“The Shop Around the Corner”) was reportedly Ernst Lubitsch’s favorite screenwriter.

PETER BOGDANOVICH, OF ‘PAPER MOON’ FAME, DEAD AT 82

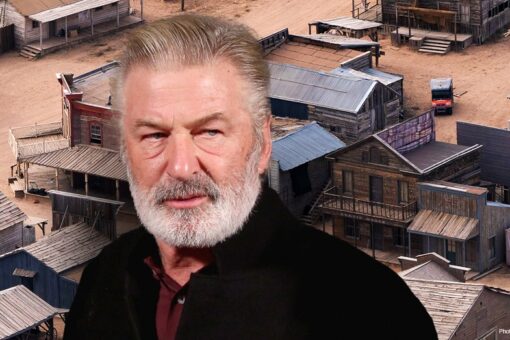

Bob Rafelson appeared in the 2010 documentary “America Lost and Found: The BBS Story.”

(Doris Thomas/Fairfax Media via Getty Images)

Rafelson studied philosophy at Dartmouth College, where Buck Henry became a close friend. He worked as a disc jockey, edited translations of subtitles for Japanese films and, in 1959, became a story editor on David Susskind’s “Play of the Week” TV series, where he wrote “additional dialogue” for writers like Shakespeare and Ibsen. In 1963, Rafelson was fired after a heated dispute with MCA’s Lew Wasserman over the short-lived series “Channing.” Reportedly, he was personally escorted off the Universal lot by Wasserman.

Rafelson’s marriage to Toby Carr, the production designer on his early films, ended in divorce. His life was also marked by tragedy when his 10-year-old daughter, Julie, died after a propane stove exploded in his Aspen home in 1973. It “affected everything Bob ever did after that,” Henry said about his friend.

After the 1970s, Rafelson turned to moody noir pictures. In addition to “Postman” with Nicholson and Jessica Lange, he directed 1987’s “Black Widow,” starring Debra Winger and Theresa Russell. Both films saw healthy box office in Europe, where Rafelson’s reputation remained in high regard. The 2002 crime thriller “No Good Deed” starred Samuel L. Jackson, Milla Jovovich and Stellan Skarsgard but barely opened in the U.S.

Rafelson received some good notices in 1990 for “Mountains of the Moon,” about explorer Sir Richard Burton, but 1992’s “Man Trouble,” which reunited the director with Nicholson and “Five Easy Pieces” screenwriter Carole Eastman, and 1998 HBO TV movie “Poodle Springs,” with James Caan as detective Philip Marlowe, did not fare well with audiences or critics.

JAMES CAAN, ‘GODFATHER’ STAR, CAUSE OF DEATH REVEALED

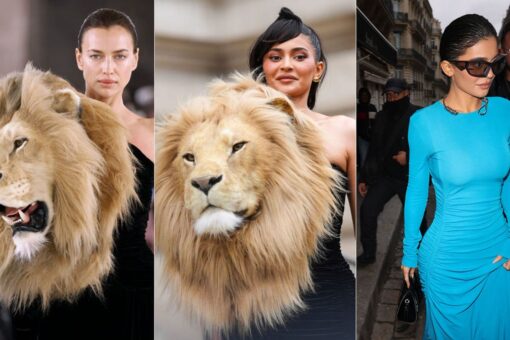

Micky Dolenz, the last living member of The Monkees, issued a statement following Bob Rafelson’s death.

(Scott Dudelson/Getty Images)

Rafelson also directed the music video for Lionel Richie’s 1983 hit “All Night Long (All Night),” matching the infectious pop ballad with a colorful, abstract portrait of a sunset block party.

Along with “Five Easy Pieces,” which was selected for preservation by the Library of Congress in 2000, and his work as a producer for BBS, Rafelson will be remembered for boosting the early careers of actors such as Jeff Bridges and Sally Field in “Stay Hungry” and Ellen Burstyn, whom he recommended to Peter Bogdanovich for “The Last Picture Show.”

Looking back on his own career in a 2004 interview, Rafelson was philosophical: “If it happens that people respond to your work in your lifetime, well, you’re very lucky… it gives you permission to go on making movies. But if you don’t get the applause, well, there are other things. I mean, after all, there’s your life to live.”

Later in his life, Rafelson appeared in the 2010 documentary “America Lost and Found: The BBS Story.”