Michael Lang, the co-creator and organizer of 1969’s Woodstock Music and Art Fair, and its follow-ups Woodstock ’94 and the ill-fated Woodstock ’99, died Saturday at the age of 77 at Sloan Kettering in New York City. The cause of death was a rare form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, according to family spokesperson Michael Pagnotta.

He last appeared publicly just before the COVID pandemic hit around the 50th anniversary of the festival, which was marked by controversial will they-or-won’t attempts to stage a Woodstock 50 festival that played out in the press.

Lang was raised in Brooklyn and attended college in New York City before jumping into concert promotion in the late 1960s. The first multi-artist event he organized was the 1968 Miami Pop Festival, which featured Jimi Hendrix, Frank Zappa and John Lee Hooker, among other acts of the era.

His move to the Woodstock, New York area sowed the seeds of a more ambitious three-day festival. Along with co-founders John Rosenman, Artie Kornfeld and John P. Roberts, they conceived of Woodstock, one of the most impactful events in music history, drawing some 400,000 people to a farm (owned by Max Yasgur) in Bethel, New York and shutting down the New York State Thruway as scores left their cars stranded and found other means to arrive to the festival grounds.

‘WHO CAN FORGET?’ WOODSTOCK: THE 10 MOST ICONIC MOMENTS FROM 1969

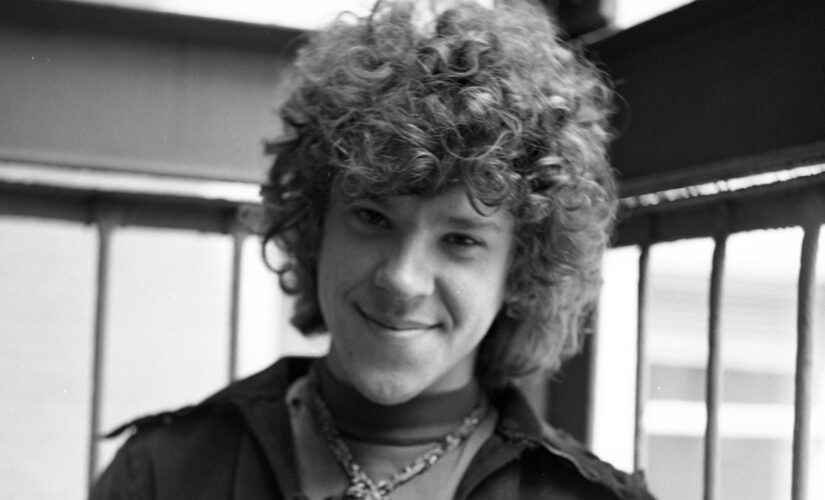

Woodstock Music Festival co-founder Michael Lang poses for his first ever public relations portraits on May 23, 1969, in New York. (Photo by Don Paulsen/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

Woodstock itself arrived at a time of great social upheaval in the United States, which was engulfed in an unpopular war in Vietnam that saw many thousands of young adults drafted and subsequently killed in Southeast Asia. Meanwhile back at home, the hippie movement was influencing art, fashion, film and music, as the tagline to the festival — “An Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music” — illustrates.

The festival exceeded all expectations — and everyone’s worst case scenarios — when a mini-city spontaneously erected to take in the tunes, and many mind-altering substances, throughout the three-day showcase. Among the 30-plus bands on the bill were: The Grateful Dead, The Who, Santana, Sly and the Family Stone, Joan Baez, Hendrix and Jefferson Airplane. A 1970 soundtrack album and documentary film, in which Lang was featured extensively, detailed the scheduling snafus, weather issues and general lack of preparedness for what would turn out to be the seminal cultural moment of the 1960s.

There were plenty of drugs being consumed over those three days. Lang recalled one incident to Variety, when Jerry Garcia passed some acid to Carlos Santana, who thought he had several hours before he had to perform, and then was rushed onstage, high as a kite, only to deliver one of the weekend’s most compelling performances.

“He battled that guitar because he thought it was a serpent,” said Lang.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR THE ENTERTAINMENT NEWSLETTER

The crowd at the Woodstock music festival, August 1969. (Photo by Ralph Ackerman/Getty Images)

Woodstock as a pop culture phenomenon, and a baby boomer rite of passage, would extend many years beyond 1969. Look no further than the enduring punchline, uttered by comedian Robin Williams and countless others in the coming decades: “If you can remember Woodstock, you probably weren’t there.”

It was also immortalized in song, notably Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young’s “Woodstock” (written by Joni Mitchell) off the 1970 album “Deja Vu,” and even as recently as 2017, when singer Lana Del Rey released “Coachella – Woodstock in My Mind.”

Woodstock was so powerful as a name that Lang was able to stage two anniversary shows in the coming decades. In 1994, to mark its 25th birthday, Lang co-produced Woodstock ’94 in Saugerties, NY, about 70 miles from the original Bethel site. The festival came to be known as Mudstock after the second and third days of the festival were marked by rainstorms that turned much of the field into a giant mud pit, further memorialized by members of Nine Inch Nails, Green Day and Primus either drenching themselves in mud or having it slung at them by the crowd. The lineup included a mixture of legacy performers from the original festival, like Santana, Crosby, Stills and Nash, Joe Cocker, John Sebastian and Country Joe McDonald, and contemporary alt-rock bands like the Cranberries and Red Hot Chili Peppers.

Another commemoration of the festival, Woodstock ’99, was held at a third site altogether, in Rome, NY, and drew about 400,000 attendees in person and many more who watched via pay-per-view. While shy of the gate-crashing and mass muddiness of the ’94 festival, the festival made news for the violence and vandalism of the audience, with Limp Bizkit’s “Break Stuff” becoming the unofficial theme song of a festival destined not to be remembered as emblematic of peace and love. None of the original artists from the 1969 Woodstock were given entire sets this time, although some individual musicians returned as part of others bands. With a distinct emphasis on hip-hop and modern rock, performers included Rage Against the Machine, DMX, Kid Rock, Dave Matthews Band and Metallica as well as a handful of veterans. The lingering bad taste involving the commercialism and reports of sexual assault created difficulties for Lang when he looked toward mounting yet a fourth Woodstock festival in 2019.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Woodstock Music Festival co-producer Michael Lang attends a celebration of the 40th Anniversary of Woodstock at the at Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Annex NYC on August 13, 2009, in New York City. (Photo by Michael Loccisano/Getty Images)

Responding to media suspicion and criticism of the two 1990s festivals, Lang distinguished between the legacies of the two. “I can understand (criticism of) the ’99 edition for what happened at the end, but ’94 was fantastic,” he told Pollstar, citing the performances in 1994 by Nine Inch Nails, Green Day and Sheryl Crow.

In 2019, Lang’s ultimately unsuccessful attempts to produce a 50th anniversary Woodstock festival suffered a series of insurmountable setbacks after announcing a bill of heavy hitters that was to include Jay-Z, Miley Cyrus and Dead and Company performing Aug, 16-18 in Watkins Glen, NY. Backers of the Woodstock 50 festival — financial partner Dentsu and its investment division Amplifi — pulled their support in April after an initial investment of more than $32 million, setting off lawsuits. But Lang’s biggest problem was getting permits from local authorities, which were short in coming even after a change of location and a capacity finally set at a lowly 75,000 before Lang finally gave in and pulled the plug.

Said Lang of its demise when speaking to Variety in August 2019: “It was just one bizarre thing after another, but I definitely feel lighter.”

Michael Lang is survived by his wife Tamara, their sons Harry and Laszlo, and his daughters LariAnn, Shala and Molly. (Photo by Frank Giorandino/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

Lang still believed that Woodstock and the counterculture it represented was an incubator for social changes leading up all the way up to the present day. “It wasn’t just entertainment; it was more about the social issues. They were part of our generation,” he told Pollstar. “Woodstock offered an environment for people to express their better selves, if you will. Give them that, and it seems to work. It was probably the most peaceful event of its kind in history.” He allowed that, originally, “it was a commercial venture meant to make money for our partners.” But ultimately, he added, “The first Earth Day came right after Woodstock. Women’s rights… Then there was the inauguration of Barack Obama, Washington’s Woodstock. Those are things that grew out of those times and evolved. Two steps forward, one step back, sometimes three steps back.”

Lang is survived by his wife Tamara, their sons Harry and Laszlo, and his daughters LariAnn, Shala and Molly.